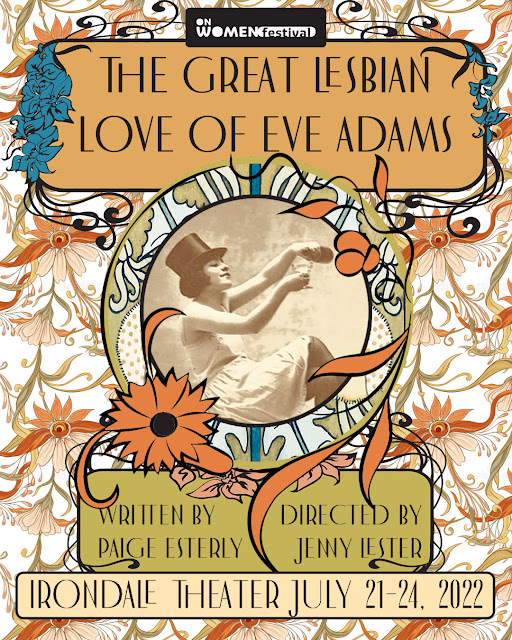

Review: "The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams" Pays Stirring Tribute to a Path-Breaking Woman

The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams

Written by Paige Esterly

Directed by Jenny Lester

Presented by Paige Esterly and Jenny Lester at The Space at Irondale

85 South Oxford St., Brooklyn, NYC

July 24, 2022

Eve Adams is less well known than comparably important figures in queer history, and Paige Esterly's new play The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams helps to continue to change that by bringing a new version of her story to the stage. The first biography of Adams, The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams, which was published only last year, contains the full text of her short book Lesbian Love, which Esterly notes in the program is "the first ethnographical depiction of lesbians in America." The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams concentrates on the period between Adams publishing Lesbian Love (in a batch of 150 copies) and her falling afoul of the New York City authorities, celebrating this iconic and iconoclastic woman and highlighting the degree to which–and the urgency with which–the same oppressive forces of state-supported heteronormative patriarchal capitalism that she defied must still be resisted today. Thanks to COVID-induced cancellations, the show was left with a single performance at its Irondale run, but it certainly made it count. The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams is part of this year's On Women Festival, which runs through the end of July and features Artists Exchange panels, streaming New Media Storytelling videos, and a trio of Mainstage Productions, of which Eve Adams was the second; the final Mainstage Production will be Letters That You Will Not Get: Women’s Voices from the Great War, which combines excerpts from the writings of American, British, European, Asian, African and Caribbean women affected by WWI with contemporary music and will play from July 29-31. [Update 8/2/22: Letters That You Will Not Get has added additional performances Aug. 4-7]

Born Chawa Zloczower in Poland in 1891, Adams immigrated to the United States in 1912 and began to go by Eve Adams (sometimes spelled Addams). When the play opens, it is 1925, and Eve (Lily Lester), who habitually dresses in 'men's' clothes, is the proprietor of Eve's Tearoom on MacDougal Street in the Village and has just received the copies of Lesbian Love. She is happily excited about being a "published author" but still wishes that could be more like her high-profile contemporary Emma Goldman–a desire that Eve's more cautious friend Viola (Princess Victome) says would be a bad idea. Viola also warns Eve, who doesn't handle heartbreak well, to be careful about Margaret (Morgan Meadows), a first-time Tearoom-gathering attendee to whom Eve is instantly attracted. Eve's friend Danny (Michael Abber), himself a queer Jewish anarchist and Eve's "pet exception" to her policy of no men at these gatherings, is less concerned than Viola with Eve's amorous pursuit (though just as uninterested in dealing with the aftermath) and more concerned that Eve is bringing Margaret rather than him to the theater the next day. The play's focus for its first half or more on the warm, funny friendship among Eve, Viola, and Danny and on Eve's attempts to woo the inexperienced Margaret builds a personal, deeply human foundation for the wider lens of the latter portion, when, since the heteropatriarchal capitalist state loves few things more than inflicting unnecessary suffering, Eve is put on trial before an immigration inspector (Loren Lester) for obscenity and indecent conduct. Her questioning by the inspector–presented as an offstage voice, keeping the focus on Eve–more directly addresses the sociocultural issues that have heretofore primarily hovered at the fringes of the queer space that Eve has carved out (as when Viola tells her not to wear pants if she is going to Midtown). Eve maintains her irreverent tone and refuses to be cowed: whatever happens to her personally, the question that she wants answered is whether the United States considers the mere existence and joy of queer women to be indecent. Eve demands to be heard, and she and the play both refuse to render her a stereotypically tragic figure, a decision that is reinforced as the play draws to a close and the lines between characters and actors erode alongside a reminder that it is more important than ever to speak out.

At one point, the characters' 1920s dancing smoothly transmutes into a pantomime of the party, a sort of fast-forward through the night in slow motion, and then segues back to dancing to a contemporary song. Visually inventive, it also reflects the sensibility of the production, which includes a few fourth wall-breaking visual jokes, a little light audience interaction, and lots of asides from Eve. Lester's Eve is effortlessly captivating, an assured, quick-witted, magnetic presence. Victome's Viola is a circumspect but caring and supportive complement to the bolder Eve, and Abber gives Danny plenty of personality, while Meadows does affecting work in conveying Margaret's conflicting layers. Eve, multiply marginalized–lesbian, Jewish, a woman, an immigrant, and involved with leftists and anarchists–tells Margaret that she does what she does because she doesn't want anyone else to have to be afraid. The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams both illuminates and contributes to that legacy. Plans are underway to bring The Great Lesbian Love of Eve Adams back to the stage (you can donate to "Eve's Transfer Fund" through the playwright's Venmo); and while you are waiting to see the play yourself, remember that we are all responsible for helping to advance towards the world, unbound by fear, that Eve imagined.

-John R. Ziegler and Leah Richards

Comments

Post a Comment